When we first moved to Chile, we were hanging out with our friends Kelly and Jake (and their kids, Veda and Aadi), who we knew in India. They mentioned that they were spending Easter at Easter Island, and we said, “We want to join you!” And so we did.

Although the island was annexed by Chile in 1888, the locals connect deeply with their Polynesian roots and prefer the traditional name of their homeland: Rapa Nui. One of the most remote inhabited places in the world, Rapa Nui is located in the Pacific Ocean, more than 2,000 miles off the coast of Chile and more than 1,000 miles from the nearest inhabited island (which actually boasts less than 100 residents).

Various theories attempt to explain how people first migrated to the island, but anthropologists today generally believe Polynesians first arrived around 300AD. The UNESCO World Heritage List website says those islanders “established a powerful, imaginative and original tradition of monumental sculpture and architecture, free from any external influence. From the 10th to the 16th century this society built shrines and erected enormous stone figures known as moai, which created an unrivaled cultural landscape that continues to fascinate people throughout the world.”

Needless to say, this mystical, isolated island has been on my bucket list for ages.

After a six-hour flight from Santiago, we arrived on Thursday afternoon and were met at the airport by a driver who draped flower leis around our necks. The whole island is only 15 miles long, and the tiny airport is located right next to the only real town, Hanga Roa. I was surprised at the size of our plane – a Boeing 787 Dreamliner – in relation to the size of the thatch-roofed airport. Later, I learned NASA had extended the existing runway to create an emergency landing destination for the space shuttle.

In just a few minutes, we reached our lovely resort, Hare Noi. “Hare” means “home” in the Rapa Nui language.

Our room was one of four that opened into a nice common space with a sectional sofa, heavy wooden table with benches, and kitchenette area. Perfect for when Tony woke up in the middle of the night. He could work on his report card comments without waking me up. The back door opened to a nice deck with chairs and tables and a view of the property. The pillars holding up our building’s roof were unfinished eucalyptus tree trunks, and our deck connected to a lighted boardwalk that led up the hill to the pool, spa, and restaurant, as well as a few more rooms up the hillside. Fat, colorful chickens occasionally wandered past, harassed by a handsome black-and-white rooster. Low walls of pockmarked volcanic stones ringed a few garden areas. In one, heavy bunches of bananas ripened on the trees with fat magenta blossoms dangling from thick, long stems. Other trees offered up guavaba, a local fruit whose delicious scent permeated the vicinity. (Soft and round with yellow skin and firm fuchsia flesh, its flavor most definitely did not live up to expectations.) Our spacious room included some interesting features, including a huge volcanic rock just outside the shower door. Toe stubbing threat, but cool nonetheless. The dome-shaped restaurant’s “walls” were really accordion doors that opened up the whole space to fresh, tropical breezes.

The path from reception to our building.

Enjoying the pool.

The population of Rapa Nui likely peaked around 15,000 in the 17th century. Today, the island has around 6,000 permanent residents, and about 60 percent are descendants of the aboriginal Rapa Nui people. According to the Polynesian Cultural Center website:

Like many of the other Pacific islands during the 18th through early 20th centuries, European diseases and indentured labor practices decimated the population. For example, as many as 5,000 islanders were carried away to work in Peru, and only a few ever returned. About 1875, 500 more were taken to work the sugar plantations in Tahiti, where a small number of Easter Islanders remain to this day. At one point in the early 1900s there were only 111 Rapa Nui people left on the island; and while the slowly growing population has managed to hang on to much of their Polynesian culture, a great deal was also lost forever. For example, the people of Rapa Nui may have been the only Polynesians to have something akin to a writing system in the form of their rongorongo tablets, a few samples of which have survived to present times in widespread museums. The ability to translate them, however, seems to have been lost forever.

More than 40 percent of Rapa Nui is a protected national park. Its dormant volcanoes, stunning shorelines, windswept denuded plains, herds of roaming horses and cattle, Polynesian culture, and delicious food were plenty to keep us fascinated and content, but the real reason people flock to the island, of course, is to witness the mysterious moai. Carved between the 11th and 17th centuries, around 900 moai were commissioned by wealthy families to honor ancestors. Ranging from six to more than 60 feet high, they were carved from scoria, which is hardened volcanic ash. Debate continues regarding how the massive sculptures were moved from the hilltop quarry to their seaside destinations and raised atop the stone foundations called ahu. Our island guides insisted the moai “walked” on a path to reach the ahu, which aligns with the most popular theory that islanders used long ropes and log pulleys to tip the moai and rock it from side to side and slowly forward, like we the way we move a refrigerator.

Topknot Quarry

Our visit kicked off with a tour of Puna Pau, the quarry that yielded only the massive circular blocks representing hair tied up in a topknot. Our guide Jojo said the red pukao would have been cut from the quarry and rolled down the hill. Stone masons would then carve and decorate the topknot before placing it on the moai’s head. The presence of a pukao indicated the moai came from a royal family, he explained. A sign at the quarry offered a couple theories as to how the 10-ton pukao was lifted to the top of a statue that could be more than 60 feet high. One theory was that workers rolled the pukao up a huge stone ramp to the statue’s head, but Jojo strongly denounced that. He said his family’s oral history confirms the other posted theory: Workers used their engineering prowess to devise a system of levers and pulleys, using huge tree trunks and heavy ropes, to raise the pukao. According to Lonely Planet, about 60 pukao were distributed to moai around the island, and another 25 remain in or near the quarry.

Meet the Moai

During our stay on Rapa Nui, we explored the sites of many ahu, raised stone altars that served as the platform for the moai statues. At some locations, the ahu was all that remained standing. At others, re-erected moai stood watch once again over the remnants of former villages. Although the original European explorers in 1722 and 1770 reported standing moai, all moai were toppled by 1864. American archaeologist William Mulloy spent 23 years leading efforts to study and restore the moai, and since then many organizations have undertaken conservation projects.

The scoria is not a very durable stone, so there is plenty of evidence of erosion. Not much keeps tourists from chipping off their own souvenirs, either. In fact, a Finnish tourist lopped off an earlobe from a moai in 2008 and was fined $17,000. Small artifacts on the ground are surrounded by a single rail fence, which does nothing to keep people out. The ahu are ringed by a barrier of thin twine and small warning signs. Our guides over the weekend told stories of ridiculous tourists who climb on or break pieces off the statues.

Ahu Akivi includes seven moai restored in 1960 by Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl and his crew of professional archaeologists. Each moai is about 16 feet high and weighs about 18 tons. While most ahu are found on the coast and face inland to watch over the villages, this one is unusual for its inland location and its mystical link to astronomy – the moai stare directly into the setting sun on the spring equinox.

Our first encounter with waterside moai was a collection of three restored ahu on the west coast. Ahu Tahai stood in the middle with a large moai. On its north side is Ahu Ko Te Riku, a moai sporting the red topknot and restored eyeballs made from white coral and obsidian. Apparently all the moai once had these eyeballs, which gave them “mana,” or a spirit empowering them watch over their clans.

On the south side is Ahu Vai Uri with five moai.

All moai faced their family’s villages, and these were no exception. On the hill leading down to the water, Jojo showed us ruins of traditional village structures. A chicken coop looked like a garage made from stacked volcanic rock with just a chicken-sized opening, where the birds would enter in the evening. The villager would put a rock in the hole to keep them inside, and nobody would be able to tell which rock was the “door.” We also saw the foundation of a typical refuge, known as hare paenga. Shaped like an overturned canoe, the heavy perimeter stones featured large drilled holes for holding a frame made of tall sticks that were covered in leaves and grass. The villagers wouldn’t have had actual homes (by today’s standards) because they spent most of their time outside, Jojo said. These refuges were only for sleeping or escaping inclement weather.

A reconstructed stone ramp led into the ocean, where villagers would have launched their boats for fishing.

Vinapu is the site of two crumbling ahu. One has mortarless blocks similar to the Incan ruins, which Thor Heyerdahl saw as evidence that Rapa Nui people originated from South America. He even built a traditional raft and sailed 8,000 miles from Peru to the Tuoamotu Islands to prove his highly disputed theory that people could have migrated from South America to Easter Island. Jojo showed us a couple moai faces poking out of the earth. He confirmed that the exposed moai are slowly eroding. One face had a piece of basalt sticking out that wouldn’t have been visible 100 years ago, he said. One of the ahu included a red block, which was a recycled top knot from a previous generation, Jojo said, explaining that when moai fell, the people would often reuse the stone to create new moai or use them for other purposes.

You see this rock everywhere. I mean, everywhere.

Right at the shoreline, the Hanga Poukura ruins included an ahu with barely distinguishable moai. But the real attraction was the tide. Huge waves crashed on the rocks. Jojo told stories of playing here as a child, riding horses bareback and encountering tourists. He and his friends would take tourists to the archeological sites in exchange for candy.

When Jojo saw how much we loved the waves, he drove us to another spot, where the waves were crazy high. They crashed dramatically over a rock and then immediately died down, creating a perfect backdrop for photos. Beach combing was also fascinating here; the rocks were weathered into lacy blocks and delicate towers.

Quick stop on the way to take pictures of the horses. Cows and horses roam freely, looking for grass among the rocks.

A sunrise visit to Ahu Tongariki is on every tourist’s to-do list here. Unfortunately, (a) at this time of year, the sun rises a little to the east of the moai, so it’s not as spectacular as it could be, (b) we were advised to go WAY too early so we waited in the dark for about an hour, and (c) I had left our national park tickets back at the hotel. Fortunately, (a) it was still a pretty spectacular experience and (b) worth the wait, and (c) a kind guard heard my plea in pathetic Spanish and let us enter without tickets.

This is the largest ahu on the island with 15 moai. They were all toppled during clan warfare, and then a 1960 earthquake triggered a tsumani that dragged the moai almost 300 feet further inland. According to Rough Guides, a Japanese news program aired footage of the Rapa Nui governor saying they could save the moai if only they had a crane. A Japanese viewer took action and ultimately set up a committee that spearheaded a five-year restoration project, completed in 1995.

We re-visited Tongariki later in the day with our guide, Tito. He swore the moai second from the right represents his grandfather. “The best one?” asked a skeptical member of our group. “Yes!” he exclaimed. I choose to believe it.

On the southern coast, we poked around the village remains next to Ahu Akahanga, where tradition holds the first Rapa Nui king is buried. Here, we saw several of the aforementioned canoe-shaped foundations of homes, as well as a pit that would have been used as an oven, a cave formed by a lava bubble, the remains of four ahu, and many fallen moai.

Tito describes how islanders cooked with hot stones in a pit.

Looking out from the lava bubble cave.

At one of Rapa Nui’s two sandy beaches, Anakena, we saw Ahu Nau-Nau and its seven moai, and Ahu Ature Huki with the first moai re-erected by Thor Heyerdahl in 1956.

From a NOVA article on the PBS website:

According to an Easter Island legend, some 1,500 years ago a Polynesian chief named Hotu Matu’a (“The Great Parent”) sailed here in a double canoe from an unknown Polynesian island with his wife and extended family. He may have been a great navigator, looking for new lands for his people to inhabit, or he may have been fleeing a land rife with warfare. Early Polynesian settlers had many motivations for seeking new islands across perilous oceans. It’s clear that they were willing to risk their lives to find undiscovered lands. Hotu Matu’a and his family landed on Easter Island at Anakena Beach.

I wore my swimsuit under my clothes for our visit to the beach, but it was a brutally windy day. I doubted I would brave the chilly air to take a dip in the ocean. However, after checking out the moai and traipsing through the powdery sand to the water’s edge, I couldn’t resist. Tony and I played in the waves with Veda, who shrieked and laughed and shared my enthusiasm for the rough water. At one point, the grey sky broke open and pounded us with cold lashing rain, but then the clouds cleared and we had warm sunny skies for the rest of our short romp.

Photo courtesy of Kelly.

Rano Raraku – the Moai Birthplace

After exploring ahu and checking out moai – both standing and fallen – all over the island, we finally visited the quarry where moai were excavated from the volcanic tuff. Tito first led us to the crater lake, site of an annual traditional triathlon. He said men had to run around the lake on foot while carrying a pole over their shoulders loaded with heavy banana stalks, swim across using woven-reed boards, and canoe in a small reed boat. About 20 moai stand partially exposed inside the crater.

The path along the outside of the crater wound past hundreds of moai in various stages of completion. Tito explained that carvers would cut the moai shape out of wall, leaving it attached by just a band of rock. After they finished, they would sever that piece, letting the moai slide down paths on the hill to begin its journey to an ahu. Tito says the moai tradition was abandoned quite suddenly, which would explain the presence of so many unfinished and forsaken statues. Some remained secured to the volcano’s walls, while others poked out of the earth at odd angles, pinned by erosion up to their necks, hiding up to two-thirds of each statue’s body.

Guide hogging, as usual.

Posing with a couple unfinished moai who never made it off the hill.

This moai, Tukuturi, is a mysteriously unique kneeling statue. Older than the others? A representation of one of the master carvers overlooking the quarry? Nobody knows.

Orongo: From Stone Men to Birdman

Deforestation, food shortages, and tribal warfare led to the decline of the ancient Rapa Nui society. According to the World Monuments Fund:

The ceremonial village of Orongo, in the south of the park, is considered to be among the most spectacular archaeological sites in the world. It is perched on a narrow ridge, with the crater of the Rano Kau volcano on one side and cliffs that fall 300 meters to the sea on the other. Orongo contains dozens of petroglyphs and stone houses dating from the Huri-Moai period of Easter Island’s history (c. 1680–1867). The self-contained, dry-laid houses featuring sod roofs were built into the topography of the site. The ceremonial center of Mata Ngarau in Orongo, center of the Tangata Manu (Birdman) cult that succeeded the moai culture, was the site for the annual games that represented the transfer of power between competing clans. By the end of the nineteenth century, most of the Rapa Nui culture had perished or had converted to Christianity; the Tangata Manu cult collapsed and Orongo was abandoned.

The Orongo visitor center included many interpretive posters and photos of the artifacts found at the site and the cult’s worship of the god Makemake. Jojo explained the bizarre ceremony that decided the island’s ruler each year during this era. After years of horrific warfare, the population had dwindled and people were tired, frightened, and ready for peace, he said. One sign of peace was the sooty tern, a bird that nested on the nearby islands. In an Amazing Race-style competition, men climbed down the hillside and swam out to the smaller islands using floatation devices woven from reeds. On the islands, they searched for nests of the sooty tern, in hopes of getting an egg. They wore a headband with a small pocket in the front to securely carry the egg back to Rapa Nui. The first warrior to return with an intact egg won, and his clan ruled the island until the next year. (Spoiler alert: This story is about to get crazy.) As a prize, the swimmer – painted in ceremonial colors – got a woman, chosen from seven beauties for having the biggest clitoris. Jojo told us the clans believed a big clitoris was associated with pleasure, and thus fertility. That was important because they needed to rebuild the population. There are even petroglyphs of symbols that represent the vulva. I am pretty sure that was the first time I ever heard a tour guide say “clitoris” or “vulva.”

Tony as a birdman.

Just outside the Orongo visitor center, we marveled at the Rano Kau volcano crater. Almost a mile across, it slopes down to a lake covered in floating totora reeds, one of only three natural bodies of fresh water on the island. Even the local dogs seemed to appreciate the view.

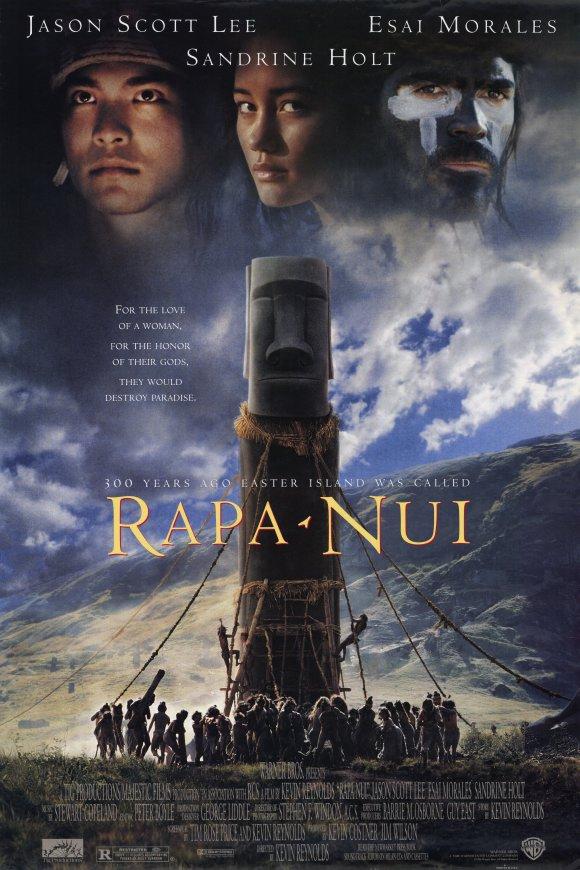

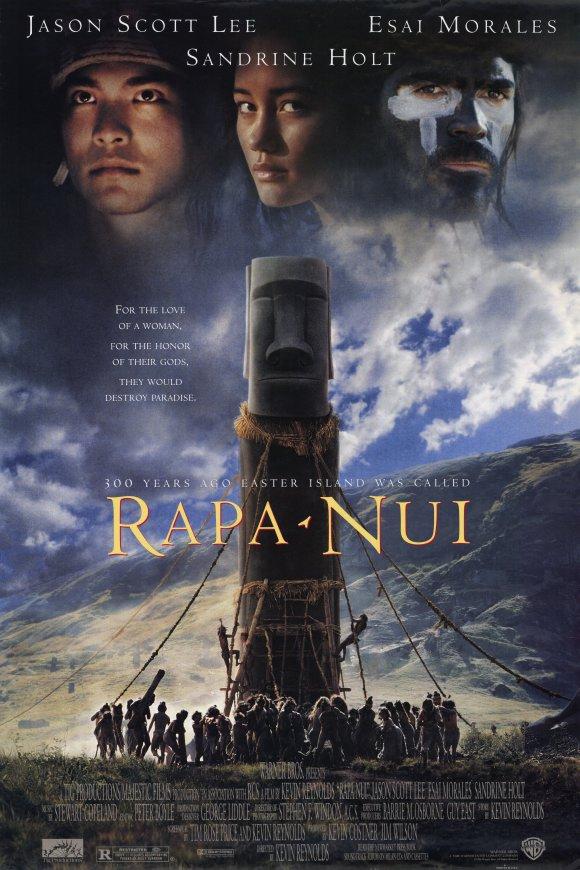

Jojo told of growing up near this crater. He ran around barefoot, chasing wild horses and picking fruit inside the caldera. When it was time for him to go to secondary school in “Chile,” he had thick calluses on his feet. He also reminisced about working on Kevin Costner’s film, “Rapa Nui,” which came out in 1994. He said many islanders participated, dressed in traditional costumes and racing up and down the volcano’s steep hillside to re-enact the birdman competition. (Side note: The movie wrongly depicts the birdman ceremony happening during the era of moai carving. The moai had been abandoned by the time the birdman cult arose.)

From IMDb.

A Taste of Culture

In addition to our island excursions, we enjoyed a lovely dinner at a waterside restaurant, Te Moana, on our last night in Rapa Nui. I had a tuna steak on a bed of mashed sweet potato and topped with an incredible medley of pineapple, veggies, and a vanilla-coconut sauce. I actually can’t stop thinking about it.

After dinner, we attended a a traditional dance show. Kari Kari featured highly spirited dancers in fabulous costumes. Women wore bras of feathers or coconuts with skirts made of long feather garlands, grasses or just a cloth wrap. Somehow they managed beautiful relaxed smiles despite coordinating crazy hip shaking with gentle undulating arm movements. Men wore variations of a loin cloth – feathers, leather flap, or just a cloth sling, and not much else. For different songs, the men swapped out their props and accessories. They wore bands of feathers on their heads, upper arms, below the knee or around the ankle, or individual grass skirts hanging from their knees, which they shook pugnaciously. They carried big threatening sticks, wore face paint, and sported many tattoos that spread over thighs and abdomen. Their athletic dances includes lots of scary gestures and facial expressions, but they always smiled and laughed between numbers, as though to reassure the audience that they weren’t going to kill us. A couple times, they pulled people on stage for an embarrassing competition. (Tony and I ducked low in our chairs to hide.) It was pretty hilarious.

Here’s a video from the Kari Kari Facebook page.

According to the website imagina Easter Island, “Most of the Easter Island music and dances are of Polynesian origin. The Rapa Nui ancestral dances have been lost or merged, though it’s still possible to find indigenous music rooted in the orally-transmitted legends that are songs and dances dedicated to the gods, spirit warriors, the rain or love.”

Easter on Easter Island

Veda and Aadi were pretty excited to find a little Easter gift from the hotel staff waiting at their breakfast table. While they ate, their dad played Easter Bunny and hid a bunch of plastic eggs filled with chocolates and raisins. (Ha! That clever bunny and his healthy habits.) The kids were adorable as they hunted for the eggs, counted them, and opened them up to find the treats. Surprisingly, the chocolates and raisins elicited an equal amount of joy.

Flying back to Santiago, Tony and I agreed this had been a wonderful trip. One tiny island managed to offer much of what we love in a vacation, and its mysterious history continues to fascinate us.

Writing this post, I found many interesting articles about Rapa Nui. Even though I wrote a ridiculously long post about our trip, there was so much I didn’t include. If I have piqued your interest, you may want to read more!

National Geographic – Easter Island, 2012

NOVA – Pioneers of Easter Island, 2000

Live Science – Easter Island (Rapa Nui) & Moai Statues, 2012

History of Rapa Nui – From Genocide to Ecocide, The Rape of Rapa Nui by Benny Peiser, Liverpool John Moores University, Faculty of Science, 2005