With only two weeks left before SUMMER break, I’m finally writing my last post about SPRING break.

Theresa had read about the Tibetan Children’s Village, and my principal had mentioned that our school was a strong supporter, but I didn’t know what to expect when we decided to check it out on April 3. Oops, we hadn’t asked for prior permission to visit.

Nevertheless, we walked up a short hill and entered a big play area, where young children in blue uniforms were eating snacks and running around. Unsure of what to do next, we found some shade and watched the youngsters until a woman pointed to the office and told us we needed to check in. Up a couple flights of stairs, we were greeted by a man who took us into the office of someone important looking. I told him that I worked at the American Embassy School and that we were interested in visiting his school. He immediately expressed gratitude for all AES has done to support the work of TCV and sent us off with a tour guide. We joined a Belgian family for a walk around the village.

Tenzin Tseten was born in India after his parents fled Tibet in the 1950s. He explained that the 1959 Chinese occupation of Tibet and ensuing protests led to more than a million Tibetan deaths and a mass exodus of survivors to India. Concerned for the thousands of children orphaned or left destitute, the Dalai Lama proposed a special center for them. The Nursery for Tibetan Refugee Children was founded in 1960 and eventually developed into the Tibetan Children’s Villages, which now manages five children’s villages and many schools, day care centers and other educational programs.

According to a TCV brochure, more than 35,000 children have received education and family-style support.

Even with so much progress, there is still much work to be done as Tibetans continue to flee the persecution in their homeland. Parents still feel compelled to give up their children by the pervasive sense of hopelessness in Tibet, where educational opportunities for Tibetan children are extremely poor. There the school system is used to suppress the cultural identity of Tibetan children by teaching in Chinese and denigrating the Tibetan language and culture.

Tenzin said parents in Tibet often face the worst of decisions: (a) bring up their children in an increasingly oppressive political climate, where their traditional lifestyle is under attack, or (b) send their children away to the TCV, illegally and permanently, for immersion in the Tibetan way of life and greater hope for future opportunities. Families pay exorbitant amounts of money for smugglers to sneak their youngsters – even infants – over the Himalayas, through Nepal and into India, often during the winter when the chance of apprehension by Chinese authorities is less likely, he said.

We toured one of the “khimtsang” or group homes, where children live as brothers and sisters with their foster parents.

Toothbrushes and soap boxes.

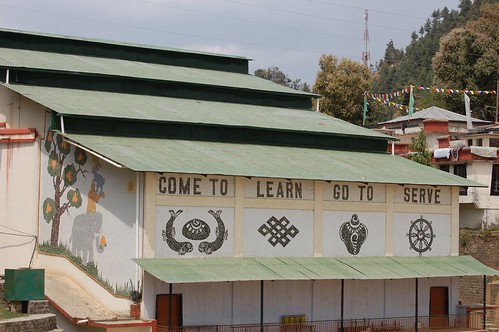

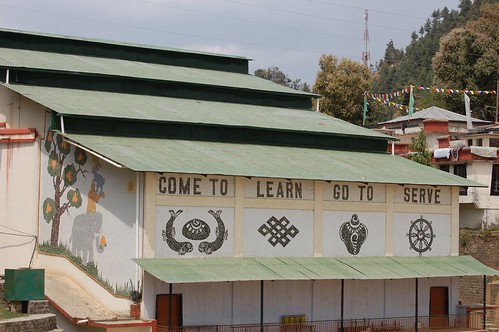

The high school field and classroom facilities.

Darn close to our own school’s motto: “Enter to learn, leave to serve.”

Temple on campus.

Om mani padme hum, a mantra in Tibetan Buddhism to invoke the attention and blessings of Chenrezig, the embodiment of compassion.

“Do you want to see the baby home?” Tenzin asked, leading us to the TCV nursery. We didn’t see any actual babies, but the toddlers were having lunch on the patio. They washed their hands at a row of sinks and then took their seats at small plastic tables with their hands folded. When everyone had been served, the teacher gave a signal and they recited a Tibetan prayer in unison before digging into their lunch.

Baby dorm.

Knowing the American Embassy School had donated thousands of books to TCV, I wanted to check out the library. Tenzin introduced us to Nancy Corliss, a retired teacher from New York, who volunteers in the TCV library twice a year for two months at a time. When she’s back in the States, she promotes the TCV’s work through speaking engagements. We arrived at the library just in time to watch Nancy read Press Here, requiring the youngsters to interact with the book. You can see in the photos that some young boys are already studying to be monks; the others wear TCV school uniforms.

A sign on the library.

When we asked Nancy to recommend a restaurant for lunch, she quickly sought permission to treat us in the staff canteen. After a nice chat and tasty Tibetan food, we carried our metal plates to the dish washer. At AES, we do that, too, but the “dish washer” is actually a “dishwasher.” Here, the dish washer was a petite lady with a big gold nose ring and a friendly smile, perched on the edge of the sink.

In addition to helping Tibetan refugees, the TCV also accepts other children whose parents want the Tibetan education. Theresa and I met a family in a Dharamsala cafe who live in Delhi but are thinking about sending their two kids to the TCV, specifically for the Tibetan Buddhism schooling. Here they are having a treat.

I still feel conflicted emotions from our time in Dharamsala. Having visited Tibet (in 2009) and seen firsthand the Chinese oppression of the Tibetan people, I grieve for the parents who send their children away in a desperate attempt to provide a brighter future and salvage their Tibetan identity. I feel a sense of hopelessness for these people, who most likely will never see their homeland again. I feel angry than I was allowed to tour Lhasa, a place of profound spiritual symbolism for Tibetan Buddhists, but my TCV guide can only dream of such a journey. Still, this town is uplifting in that it promotes Tibetan culture while providing safety and security for the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan refugees.

After describing the TCV to Tony, we decided this was a cause worth supporting. We recently committed to sponsoring a child and were assigned a 10-year-old girl named Tenzin Nordon, whose father escorted her to Lhasa before sending her on to India with a group of other Tibetans. She attends the TCV school in Bylakuppe, India. A letter from the school says she misses her parents terribly but is happy to have two cousins at the school with her.

If you’d like to become a TCV sponsor, contact Nyima Thakchoe at nyima@tcv.org.in. And tell her I sent you!